Pre-Columbian Art

Francisco Matto and Pre-Columbian Art

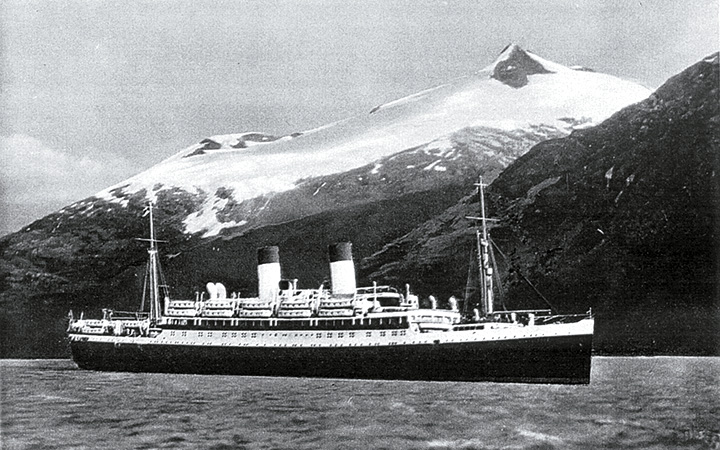

From a very early age Matto was profoundly attracted by the artistic production of the ancient inhabitants of the Americas. As early as 1932, at the age of barely twenty-one, he traveled to Tierra del Fuego and from there to Osorno, in Chile, deep in Mapuche territory.

It was then that he began his collection of pre-Columbian art, a passion that would stay with him for the rest of his life. The indigenous religions so intertwined with nature and their magical and supernatural references fascinated him and would indelibly mark his creative process.

His collection grew constantly and passionately, and by 1946 his studio held various showcases replete with Nazca ceramics, while Wari, Chancay and Chimú tapestries hung on the walls. Being surrounded by these pieces of art had a sharp influence on his mature work. The sobriety of coloration of Peruvian vessels and textiles, "where four or five earth tones suffice to create a very controlled but amazingly rich harmony of colors," along with the geometry and the "pureness of style, where horizontal and vertical lines prevail over curves," captivated him, according to Cecilia de Torres in the 2003 exhibition catalogue Francisco Matto, Poesías y Pinturas (Francisco Matto, Poetry and Paintings), citing the artist himself.

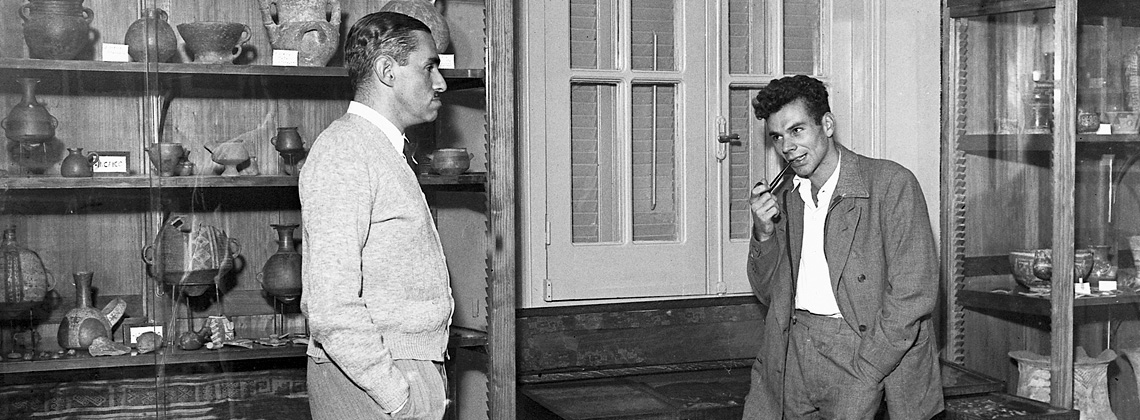

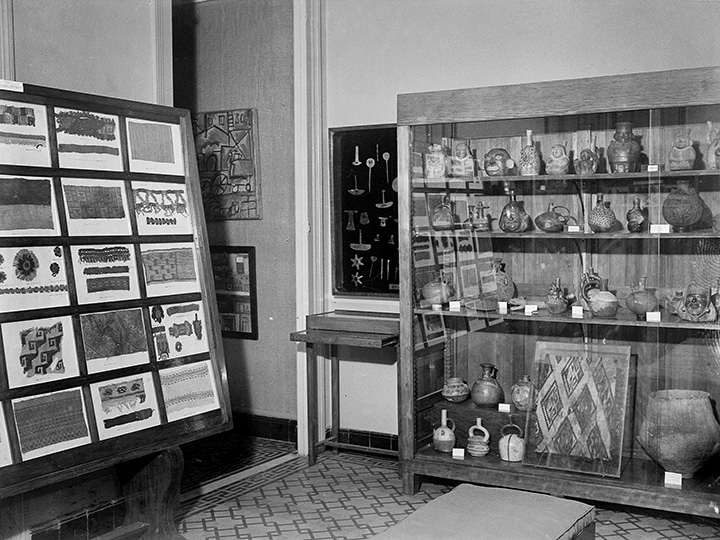

In September 1962 Matto opened the doors of his collection of pre-Hispanic pieces at the Museo de Arte Precolombino (Museum of Pre-Columbian Art) in Montevideo, in what had been the carriage house of the old Vilaró Rubio family villa located on Calle Mateo Vidal. The museum showed ceramics, sculptures and textiles from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela. Ernesto Leborgne did the installation, in which he sought to "… surround, isolate each element, so as to not suffocate each one's message," to transmit, with the right lighting, "a sort of mystery to be perceived or intuited by the viewer, the aesthetic phenomenon especially underscored in each case," according to Denise Caubarrère in the 2004 essay Arte primitivo: Estética innovadora (Primitive Art: Innovativing Aesthetic).

In 1964 Matto and Leborgne prepared a catalogue with photos by Alfredo Testoni and prologue by Esther de Cáceres, in which they explained that the pieces were presented as art and not as anthropological examples. "The pieces of art stand alone: they themselves tell of what is essential and transcendent in them. It is a museum created by an artist. And an artist knows that this experience must be direct, solitary, silent; and thus it will be fecund as an element of enlightenment, beyond its impact on intellectual or cultural life. Because it will reach other planes related to the whole and profound being."

In the introduction to the same catalogue, the authors say that the Museo de Arte Precolombino's "chief purpose is to exalt the Art of the ancient inhabitants of the Americas, affording them the legitimate place they deserve among the great artistic traditions of Humanity, as well as to collaborate with anthropological research."

The museum's creation had local and international repercussions. The Uruguayan weekly Marcha, in its August 2, 1963 edition, published Matto's words regarding Amerindian works of art. In his view, they have a continuity that runs through to the present: "The reassessment of the Americas' great past, obtained through these mute witnesses, is irremediably tied to our modernism." The Buenos Aires daily La Prensa, in its February 27, 1966 edition, published an article by Carlos Gradin titled Arte Precolombino, La Colección Matto (Pre-Columbian Art, the Matto Collection). No. 29 of the Humboldt magazine, published in Hamburg in 1967, reproduces works from Matto's Museo de Arte Precolombino collection.

The museum was an important achievement of the collaboration between Matto and its director, Ernesto Leborgne, offering the Uruguayan public access to the collection of Amerindian works, which had not been available in Montevideo until then. Major exhibitions were held, each with its catalogue. In 1967 it was La figura del hombre Americano (The Figure of Man of the Americas) including 88 Amerindian pieces of diverse origins, with an illustrated catalogue including text by José María Montero Pérez. In 1970 it held Arte Negro (Black Art), with 82 works from his collection and pieces contributed by the collectors Augusto Torres, Manolita Piña de Torres, Alfredo Cáceres, Ernesto Leborgne, Fernando Mañé, Amalia Nieto, Guillermo Wilson, Luis San Vicente and Eduardo Yepes. The illustrated catalogue includes texts and a detailed study of each piece.

In 1974, Museo de Arte Precolombino joined in the homage upon the one hundredth year of Torres García's birth, presenting an exhibition and catalogue titled Juguetes, objetos de arte y maderas (Toys, works of art and wooden pieces) by Torres García.

In 1978 the museum's doors were closed to the public.

Abbondanza, Jorge. El museo precolombino: los tesoros de América que alberga Montevideo.

El País, pág. 18.

See article in .pdf format

Homenaje a Joaquín Torres García. Museo de Arte Precolombino. Montevideo.

See catalogue in .pdf format

La figura del hombre americano. Museo de Arte Precolombino. Montevideo.

See catalogue in .pdf format

Arte Precolombino. Colección Matto. Museo de Arte Precolombino. Montevideo.

See catalogue in .pdf format