Biography

MATTO: A Magical Spirit

The firsts years

Francisco Alberto Matto Vilaró was born in Montevideo on October 18, 1911. His parents, Francisco Alejo Matto Vilaró and María Eulalia Vilaró, were cousins, both highly inclined toward the arts: his mother wrote poetry and his father was a great lover of music.

The Matto Vilaró family had two other children: Jorge and Graciela. The family lived in a villa at Avenida 8 de Octubre, between Avenida Luis Alberto de Herrera and Bulevar José Batlle y Ordóñez, surrounded by large grounds. The artist would live there until 1963.

As a child Francisco did not attend school and his education was provided by tutors at the family estate. One of them was Miss Herman, an English woman who would play a very important role in the artists education. In parallel he began taking drawing and painting classes with the artist Carlos Rúfalo. According to Gabriel Peluffo in Historia de la pintura en Uruguay, Rúfalo represented predominantly academic criteria, painting in a self-taught version of local impressionism.

Another of his teachers, Fernanda Luraghi Ponce, collected Matto's first poems in a notebook, saying that they were: "the inspiration of a child's great and dreamy soul."

Matto: travel and discoveries

In 1932 he traveled to Buenos Aires, where he bought baskets made by the Ona Indians, which would become his first pieces of Amerindian art and the beginning of his great collection of pre-Columbian art (later presented to the public at his Museo de Arte Precolombino inaugurated in 1962). From there he left on a cruise to Tierra del Fuego and southern Chile, where he visited Osorno, deep in the territory of the Mapuche tribes. The wooden funeral poles (rewes) that he discovered in the indigenous cemeteries awed him. His files contain a postcard that illustrates various totem figures planted in the ground as grave markers, which years later inspired his Tótems in painted wood. This trip to southern South America was not customary among artists and intellectuals at the time, who tended to make the inexorable pilgrimage to Europe.

César Paternosto sees Matto as:

"a pioneer artist in the context of the art of the Americas. An ethical and aesthetic attitude that contributes to recomposing what I call the cultural equation of Latin American art, given that the art of our continent has suffered from a marked imbalance: an excessive focus and dependence on the –albeit inevitable– European sources ("Latinidad") and little or no connection with the only genuine art of the Americas, the art developed before and/or in the shadow of dominant European art."

Francisco Matto: un artista de América,Bienal del Mercosur, 2007

Matto, self-taught painter

Throughout the 1930s Matto developed his own aesthetics nurtured by the avant-garde European artists he studied in foreign publications and books that reached Montevideo. In parallel with painting he continued writing poetry. At his family's villa he painted a series of murals that included his verses and a surrealist representation of roosters and fish. There is enormous coherence between his pictorial and poetic language during this period, and it could be said that his canvases are the visual rendering of his poems, where color is the materialization of his poetry's inner sound. In the autobiographical notes he wrote that in the year 1935: "he paints very flat compositions in local tone and bright colors, where blue and rose predominate. He feels a great attraction to nature; he constructs small sculptures in different materials that he places among the foliage in the garden of the villa where he lives; it is his first attempt at integrating art in nature." In another text, Matto refers to the music of Debussy (1862-1918), whose studies of the possible correspondences between music, painting and poetry had an important impact on the artists of his time.

Between 1937 and 1938 he painted three versions of Cristo crucificado (Christ crucified) based on Gauguin's famous Yellow Christ (1889). On the walls of his bedroom he painted Ojos de atún embalsamado en redoma de alcanfor y trementina (Tuna eyes embalmed in phial of camphor and turpentine), of which only a photo remains, and which was evidently related to surrealist poetry.

Around that time he began painting on wood in irregular formats, such as the work Mujer con Gallo (Woman with Rooster), and a series of religious themes that would be a constant throughout his life.

In 1939 he paints Escena Campestre (Country Scene), Interior en rosa (Interior in rose), La Quinta (The Villa), and Jardín (Garden), in which planism and frontality stand out. The bright colors, applied as he himself described "with small touches of the brush," evoke the painting of Bonnard and Matisse. He also paints scenes from everyday life: his open closet with multicolor ties hanging on the door, gardens, still-lifes, family portraits and beach scenes document the comfortable life in Montevideo in the 1930s and 1940s. On the occasion of the exhibition titled Francisco Matto, Poesías y Pinturas (1935-1945) (Poetry and Paintings 1935-1945), at the Oscar Prato gallery, the Uruguayan critic Nelson Di Maggio noted that:

"No other Uruguayan painter approached Matisse and Picasso with the respect and, at the same time, the inventive capacity of Matto. The majority preferred the lessons by Othon Friesz and André Lhote, but none of them made of Matisse's figuration (continuing on that launched by Gauguin) a language of their own, cannibalizing with special delight."

La República newspaper, October 27, 2003

Matto and literature

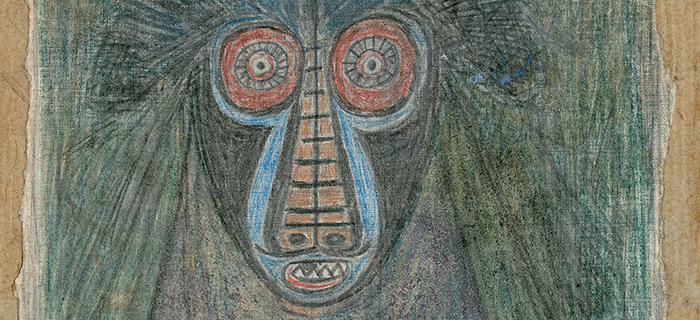

Regarding his inclination toward literature, in 1937 Matto transcribed a story titled Samba Kulung se hace caballero (Samba Kulung is Knighted) from the book The Black Decameron, based on popular African tales collected by the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius (1873-1938). In his chronology he wrote about his interest in primitive art and cultures. "In 1937, that magical spirit revealed itself in a fish rendered in iron, and later in some wooden pieces and certain paintings where there are also elements of ‘Black art' and even that of New Guinea or of the Arnhem Land aborigines in Australia's Northern Territory." This interest in the magical and the occult is also evident in a drawing of an enigmatic figure he titled Negro Ancestral Painting, whose similarity with the representations of Eleggua that Wifredo Lam painted later is surprising.

Federico García Lorca's assassination on August 19, 1936 moved Matto profoundly. In a text in which he also mentions Pablo Neruda, Matto identifies with the poet who had fallen victim to Fascism, lamenting that artists were targets of persecution. He also lashed out against society's injustices in his illustrated poem Oda al Lampeão, (Virgulino Ferreira, alias Lampeão, or Lantern, was a bandit killed in 1938 who inspired terror in the Brazilian northeast). This poem was published in 1944 in the Argentine magazine Verde Memoria, in a special edition devoted to Uruguayan poetry, along with poems by Mario Benedetti and Amanda Berenguer, among others.

In 1943 he wrote Carta pictórica. La Geometría en el arte moderno (Pictorial letter. Geometry in modern art), a subjective study on the evolution of painting, including pre-Columbian art, Giotto and Picasso, that presaged a major change in his work. Despite the subtitle referring to geometry, the illustrations are figures sunbathing on the beach, but the literary style is different. He no longer uses the surrealist and symbolist metaphors characteristic of his earlier writing. In the text it can be seen that, for Matto, Cézanne is a key modern figure, for having introduced geometry and order, who does not eliminate emotion but instead supports it with intelligence. The consequence was Cubism, "a reagent, a revolution," from which no modern escapes.

Matto and Constructive Art

In April 1934 Joaquín Torres García arrived in Montevideo and founded Estudio 1037, which as of 1935 would become the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (Association of Constructive Art), bringing together a large number of contemporary Uruguayan artists. During those years Matto was already involved in the Montevideo art world: he was a friend of the painter Pesce Castro, of the sculptor José Luís Zorrilla de San Martín, of the poet Susana Soca, and of the architect Ernesto Leborgne, who was already attending Torres García's lectures.

Between 1937 and 1938 Matto frequented the Arte Constructivo group's exhibitions and attended Torres García's talks."Until 1939 I was a self-taught painter," wrote Matto. That year he met Torres García:

"I got to Torres' place because there had been a lecture. And at that point I said to myself: this is my moment, finally I am going to be able to talk with Torres. Two days after the lecture I mustered the courage and went to see him. I was trembling when I got there, because I was going to talk to the giant; I took two little paintings of mine with me, rang the bell, and Torres appeared. He put one painting on the easel and one on the floor. He looked at them and said: «Keep on painting the way you are painting now, until I tell you not to, that's enough.» And five months went by. I was delighted that he allowed me my independence, that I did not have to follow certain rules. He allowed some of us certain freedoms."

Carlos Cipriani López. Con Francisco Matto / Las fuentes de lo mágico.

El País newspaper, March 12, 1993

Torres' school, Taller Torres García, was created at the outset of 1943, and Matto became one of its founders, along with the brothers Edgardo and Alceu Ribeiro, Augusto and Horacio Torres, among other artists. As of that year he was involved in almost all of the exhibitions held by the Taller.

Two years following the Taller's creation, from Paris, Jules Supervielle and François Gilles de la Tourette, curator of the Petit Palais and the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, wrote to him, inviting him to show his early works in Paris. Matto declined the invitation because he was then engaged in a new cycle of his art that was taking him to Constructvie Universalism. In fact, his first paintings in the Constructive aesthetic are from that period. On this change in his painting Matto wrote in third person in Variantes formales en el arte de los Tihuanaco (Formal variants in Tihuanaco art), a study on pre-Columbian Peruvian ceramics, from the aesthetic viewpoint. The original manuscript is held by the Getty Foundation for Research. There he noted: "In the mid-1940s the influence of Torres García becomes more evident in his work. The orthogonality of Torres' works and their metaphysical tone have a big impact on him. The direct study of the art of the Altiplano also had a profound influence on his work. Torres-García, on the one hand, and Amerindian art, on the other, led him to orthogonality. From then on he would prefer verticals and horizontals to build his structures, which would become increasingly frontal, in a very synthetic way."

When Matto visited Torres García he had the opportunity to see the trilogy Pachamama, Inti e Idea (Pachamama, Inti and Idea) (1942-1944), wooden figures referring to Incan deities that the master had placed in the garden of his house at Calle Abayubá. These works surely impacted Matto because of their rustic texture and their connection with Amerindian art. In 1948 Matto built pieza geométrica (geometric piece) from wooden boards painted red, in which the Taller's constructivism fuses with Amerindian art, aiming at constructing sculpture with architectural dimensions.

Matto's relationship with the Taller Torres García led him to teach there for a brief period in 1955, during the absence of Julio Alpuy, who had been teaching since 1945. In a letter to Matto dated in Paris on October 7, Horacio Torres says:

"They've written to me saying that you are teaching classes at the Taller. Congratulations! Surely the rest will be good for Alpuy, who has worked so much. I would like to hear from you about how it's going, how the students are doing, and what you are painting...".

The Taller continued to function, following Torres García's death in August 1949, until the mid-1960s.

Travel

Francisco Matto made numerous trips over the course of his life, in addition to his pioneer South American journey. In March 1950 he traveled to Europe, and particularly to Rome, where he met up with Augusto Torres, who was ill, and for whom he sought medical attention. Once Augusto recovered, the two traveled together to various European cities, sharing their enjoyment of the works and artists they considered the great masters of art. During this trip he visited Paris, where he met the director of the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro, Paul Rivet. In March 1954, when he married Ada Antuña Zumarán (1916-2015), he traveled to various European countries with his new wife.

Later, in 1958 he traveled to Europe. He went to southern Italy, visited Paestum and spent a month in Sicily, where he saw the Greek temples at Segesta and the Selinunte valley. His interest in classical style is reflected in a series of paintings of figured friezes.

In 1971 he traveled to New York to attend the Joaquín Torres García retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum. He went on to Europe and Greece, with a visit to Delfos, which left him with particularly lasting memories.

He returned to New York in 1986 for the opening of the Torres García and his Legacy show at the Kouros gallery, where he met up with his companions Gonzalo Fonseca and Julio Alpuy.

Matto and the critics

At the first Municipal Visual Arts Salon held in Montevideo in 1940, Matto showed Retrato de JMV (Portrait of JMV) and La Guerra (War) in which a figure pleading before an indifferent soldier describes his feelings about World War II. In the El Bien Público newspaper, the poet Ernesto Pinto, who signed his art criticism as "Restone," wrote about La Guerra:

"Francisco Matto is another of this salon's scant revelations and affirmations. He has imitated no one. And allowing himself to be swept away by his own ideas, this cultured and controlled young man has constructed a surrealist canvas. He is the only one, among all the rest, who seems to have heard the roar of the cannons that are destroying not merely the homes of Europeans, but the entire spiritual culture of the world."

El Bien Público, 1940

The Argentine professor Jorge Romero Brest, in his Crítica del primer Salón Municipal de Artes Plásticas (Critique of the First Municipal Visual Arts Salon) wrote of the "advanced Picassian surrealism" of Matto's painting, and noted the anguish and aloneness in figures like Mujer del traje a rayas (Woman in striped dress) which Matto showed at Uruguay's 4th National Salon that same year, along with Rincón del Parque (Corner in the Park).

As of the First Montevideo Municipal Salon, Mattos began participating in salons and showing his work assiduously. In 1941 he showed Caín y Abel (Cain and Abel) at the 2nd Montevideo Municipal Salon, and La silla roja (The red chair) at the 5th Uruguayan National Salon. In May 1942, undoubtedly encouraged by Torres García, Matto showed at the Amigos del Arte association, along with Augusto and Horacio Torres. The exhibition, recommended as "among the most suggestive and instructive of the season," must have stood out for the sharp difference in style among the three artists. According to Carlos Fríes, critic for the El País newspaper, Matto painted "a completely heterogeneous Nature, in joyful, luminous, bright colors. The colors dance, the contours vibrate, the style sparkles, the tones shine, the painted objects speak, shout, sing lyrically." Matto showed twelve oils: Mujer con un gallo (Woman with rooster), Paisaje (Landscape), Interior con tres mujeres (Tres mujeres españolas) (Interior with three women / Three Spanish Women), Naturaleza muerta (Still life), El ropero (The closet), La playa (The beach), Sagrada familia (Sacred family), Figura con un gallo (Figure with rooster), two Motifs de Las mil y una noches (Motifs from The Thousand and One Nights), Mujer sentada (Woman seated) and Paisaje (Landscape).

On October 15, 1957 he opened a show with Augusto Torres at Galería Moretti. Matto presented an oil from the Piccadilly Circus series. "Matto addresses the spatial relationships and accentuates light effects; the atmospheric effect, which he certainly does not respect as a naturalist attribute, becomes a key vehicle of composition in his work. This allows for the richness of tones and the energy of the images.

(Unsigned. La actividad plastic. Exposición Matto – Torres.)

In 1960 he sent two constructions in wood and an oil on cardboard titled Nueva York (New York) to a Taller Torres García group show at The New School for Social Research, organized by Gonzalo Fonseca in New York. As Alicia Haber notes, that year Matto began isolating the signs from the structure in his wooden pieces. Mari Carmen Ramírez also points to the same process in the cement works that Gonzalo Fonseca was doing at the same time in New York, although clarifying that:

"... in no work can the exploration of the independent qualities of the sign be so well appreciated as in the monumental wooden constructions that Francisco Matto began doing at the outset of the 1960s."

La Escuela del Sur – El Taller Torres García y su Legado, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Pg. 126.

As of 1960 Matto did totems in painted wood. On them, the critic Robert C. Morgan wrote in his article Francisco Matto / The persistent force in art, included in the exhibition catalogue for the 2007 Mercosur biennial: "Although Matto's sculptures are often perceived in a frontal manner, we may read them as having dimensions. We may soon discover our sense of time has become less fixed, our awareness of temporality more indeterminate. It is conceivable that by allowing such art to cast its spell, the viewer may see them on a different level than expected. Is it possible that such forms can incite a mystical event in time, a fresh look at the world, an intimacy with nature that people who lived thousands of years ago may have understood as being within time, instead of feeling anxious about the hypothetical present?"

In April 1989 in the exhibition space Subte, Salón Municipal de Exposiciones, Alicia Haber organized the exhibition titled Matto. Obra Monumental (Matto. Monumental Work). In her essay, Estructuras Mágicas (Magical Structures), Haber points out that the monumental facet is very relevant in Matto's creative path.

"When I walked into the show I was hit in the face by a breath of greatness. It had been a long time since I had seen such a tight display of works of such high plastic value, severe, essential, alien to all frivolous novelty, pure, powerful and, above all, highly sensitive"

Horacio Roldán, El País, May 21, 1989

Elisa Roubaud, in Lo universal en el arte (The universal in art), noted the "rigorous essentiality" of Matto's creations, where "aesthetic emotion and knowledge come hand in hand. It's all simple. Like children's speech is simple. The reasons of nature." El País, 1989.

In Matto: Pinturas y Esculturas (Matto: Paintings and Sculptures), a publication produced by Matto in 1991, the Uruguayan artist and critic Anhelo Hernández wrote that in Matto's work there is an objective reality, in opposition to a pragmatic approach. According to Hernández, Matto offers "the existence of another world that is presented as primarily tangible, without distance, which in that aspect is differentiated from the world of visuality."

Public projects

In 1964 Voldney Caprio, director of Manuel Rosé High School No. 1 in the city of Las Piedras, Canelones, Uruguay, invited several Taller Torres García artists to create constructive works to decorate the building. Matto contributed an adobe relief and a constructive vitraux. Other members of Taller Torres García also participated: Horacio Torres (his work was lost), Manuel Pailós, Augusto Torres, Dumas Oroño, Ernesto Vila and Julio Mancebo.

In 1969 the Central Bank of Uruguay invited Matto to design a coin, in adherence to the Coin Plan supported by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Together with Ernesto Leborgne they prepared a plaster mold based on the circular compositions Matto was doing at the time. It was coined in 900 silver at the Casa de la Moneda mint in Chile. Its value was 1,000 Uruguayan pesos and it circulated for a few weeks in Uruguay. In 1971 it was recognized by the German numismatic association Gesellschaft Für Internationale Geldeschichtele as the most artistic of the coins minted that year worldwide.

In 1982 Matto did a U-shaped sculpture in reinforced concrete, three meters high, installed at Paseo de las Américas, Punta del Este, Uruguay, in the context of the first Modern Open-Air Sculpture Encounter. Other invited artists were: Nelson Ramos, Hermann Guggiari, Gyula Kosice, Ennio Iommi, Jacques Bedel, Mario Irarrázabal, Waltercio Caldas and Edgar Negret. In the El País newspaper, Matto noted that he wanted his work to be whitewashed, "because it is an element that gives life, not a perfect white." Hence he rejected the use of synthetic paint. "I want the work to be enriched by the patina that time gives to the lime, and when necessary give it another coat of whitewash to start the process all over again."

The 1st International Art Festival took place in Medellín, Colombia, in 1997. For the program Espacio Público, una Construcción Colectiva (Public Space, a Collective Construction) 25 artists from different countries were invited, whose works were installed at various sites in the city. Francisco Matto was invited to participate in this event, and his reinforced concrete work Formas y Figuras (Forms and Figures),1993, six meters high, was set in Parque El Ajedrez, in the Santa Mónica neighborhood.

In 1996 a replica was made of his sculpture Formas (Forms), to be placed in the sculpture park at the Edificio Libertad building in Montevideo.

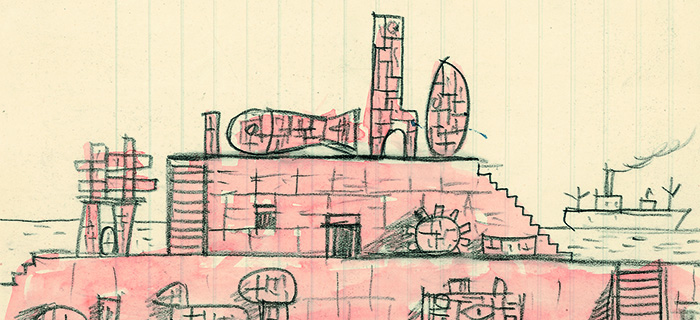

One of Francisco Matto's most ambitious projects was the creation of a community for artists. It was to be a development devoted to art for the Taller Torres García artists at Belastiquí, a property owned by the Matto family on the banks of the Santa Lucía river. In 1948-49 Matto did sketches for a project of dwelling-studios and brick sculptures. The buildings were to be done in bricks produced in the community's own oven. He never managed to carry out the project, which would have been an important cultural center and a nonpareil aesthetic and cultural asset.

Olga Larnaudie noted, shortly before Matto's death:

"With a body of work whose continuity and coherence is clear over the course of decades, this artist takes from the Torres García legacy aspects that he transforms as he delves deeper into them. His relationship with ancient art, and with primitive zones of contemporary expression, ceases to be a mere slogan and becomes a vital confluence. From being a sign of all-encompassing coexistence in time and in space, it comes to be a way of apprehending that takes on the dimension of a spiritual communion, thereby attaining, through form, what he considers essential in humanness. A return to the essential."

Arte y Diseño, El País, Montevideo, November 1994, p. 7.

On September 15 1995 Matto died at the age of eighty-three. In the Uruguayan weekly Brecha, Anhelo Hernández paid a moving homage to the artist. "He was not a theoretician. Any attempt to take that route sufficed for him to start whistling a Bach air or praising Stravinsky. But that doesn't mean that he didn't elaborate, time and again, a thinking that he strove to make clear and concise, to serve him as guide."

Compilation of texts by Cecilia de Torres published in Francisco Matto / Poesías y Pinturas, 2003, and Francisco Matto / El Misterio de la Forma, 2007.