Work

Paintings, sculptures, drawings and objects.

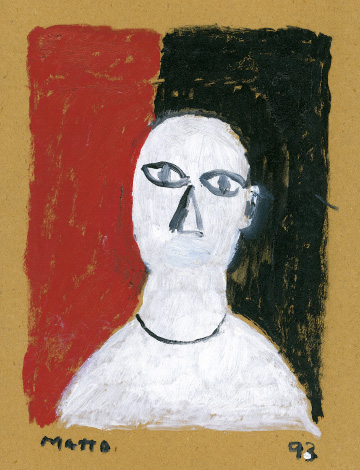

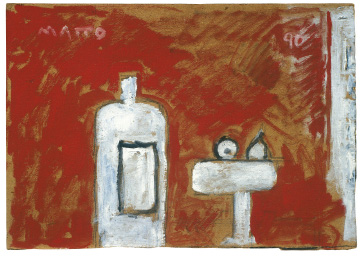

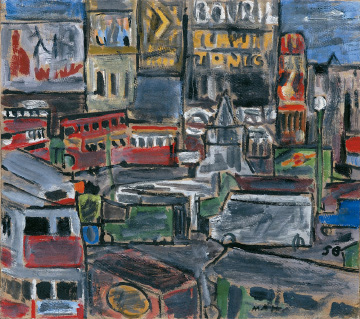

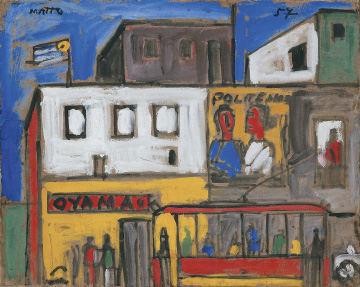

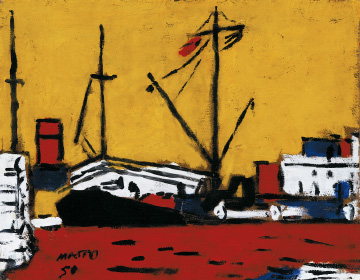

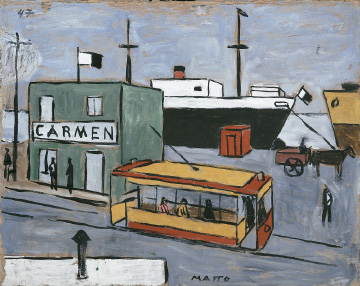

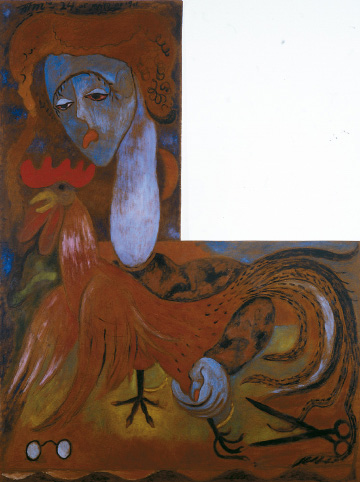

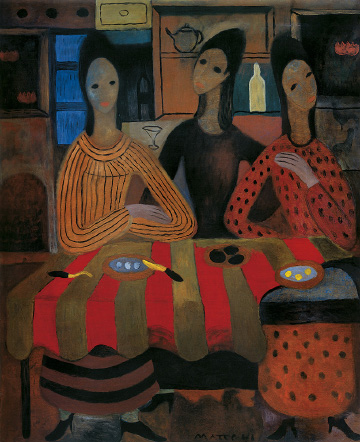

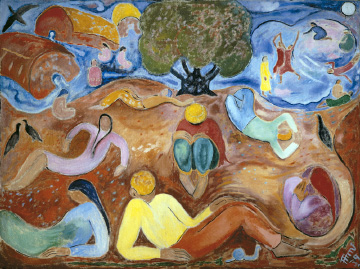

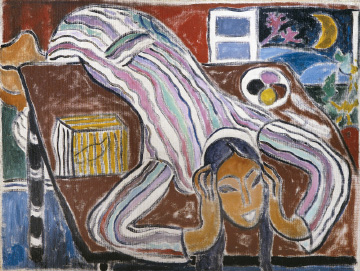

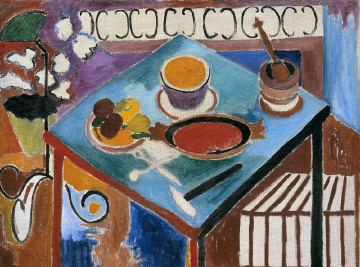

Until 1939 Francisco Matto was a self-taught painter. The pictorial legacy of Matisse and Gauguin is present in the vibrantly colored canvases of that stage of his work.

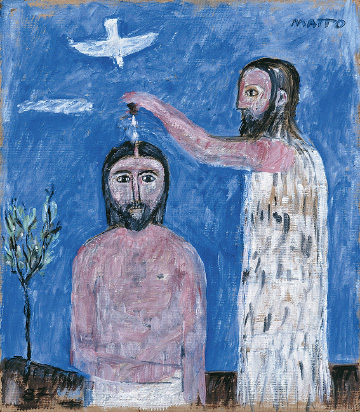

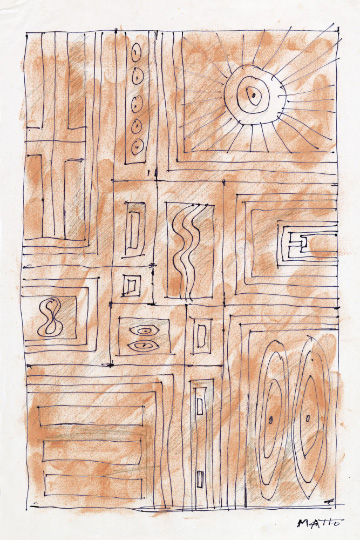

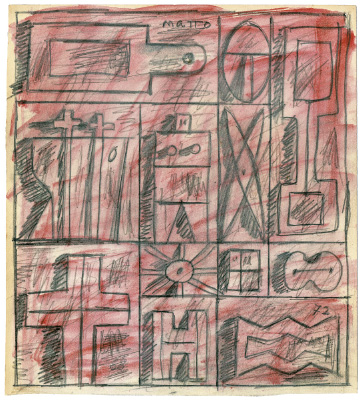

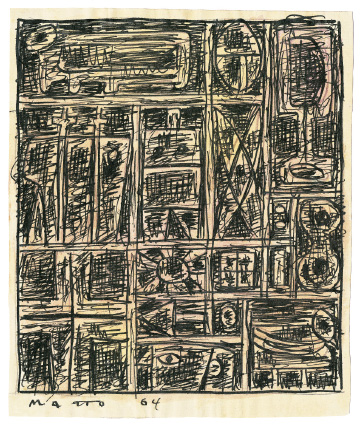

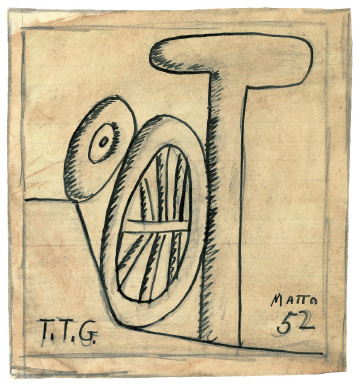

The poetry he writes simultaneously in a surrealist vein maintains strong coherence with his painting, and the close relationship between the two is more than evident.

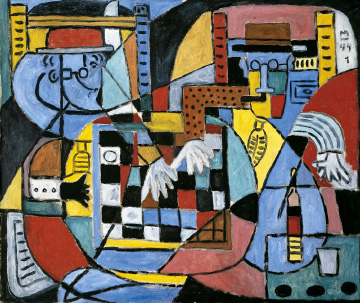

As noted by the critic Nelson Di Maggio, "no other Uruguayan painter approached Matisse and Picasso with the respect and, at the same time, the inventive capacity of Matto. The majority preferred the lessons of Othon Friesz and André Lhote, but none of them made of Matisse's figuration (continuing on that launched by Gauguin) a language of their own, cannibalizing with special delight" (La República newspaper, October 27, 2003).

In 1939 Matto met Joaquín Torres García and began showing him his paintings.

According to Matto himself, Torres encouraged him to go on painting as he had been, and recommended only that he continue painting “in a planar way and with local colors," unlike what Torres taught and demanded of the rest of his students.

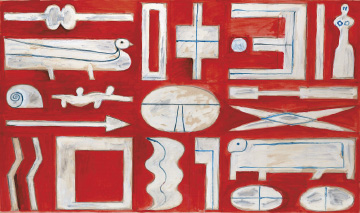

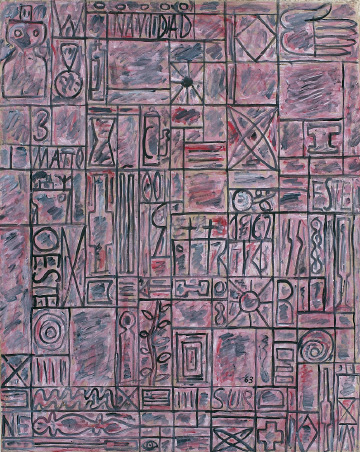

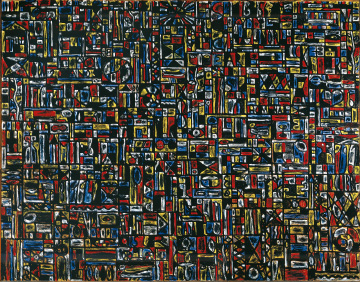

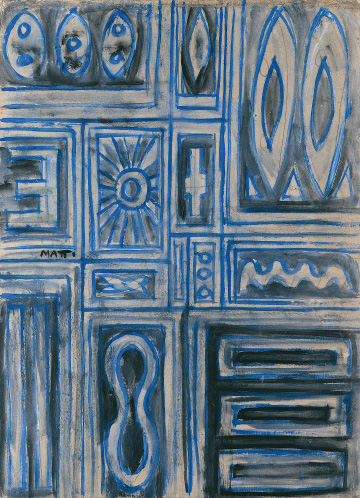

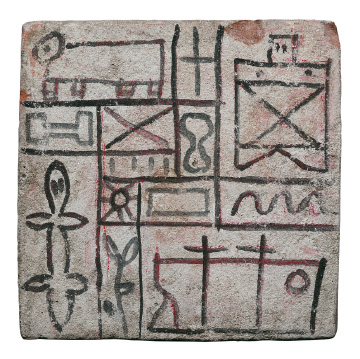

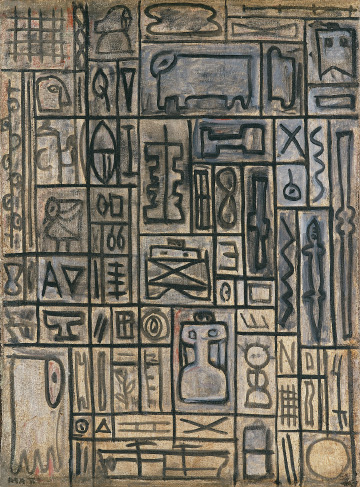

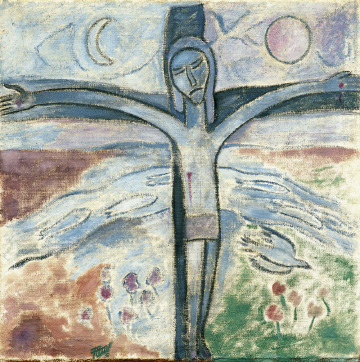

According to Cecilia de Torres in the 2003 exhibition catalogue Francisco Matto / Poesías y Pinturas (Francisco Matto / Poetry and Paintings): "He then began abandoning the light and colorful visuality inspired by the Paris school. His painting gradually evolved toward the asceticism, structure and rigor marking his later work. Moreover, his interest in Amerindian art found an echo in the ideas then being debated at the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (Association of Constructivist Art) and Taller Torres García, to find an art firmly rooted in the pre-Columbian past of the Americas."

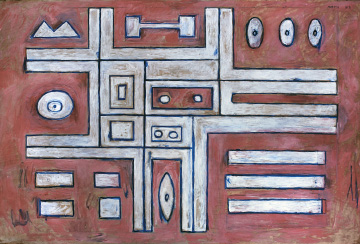

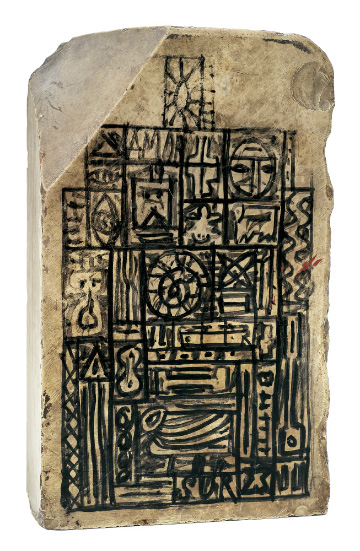

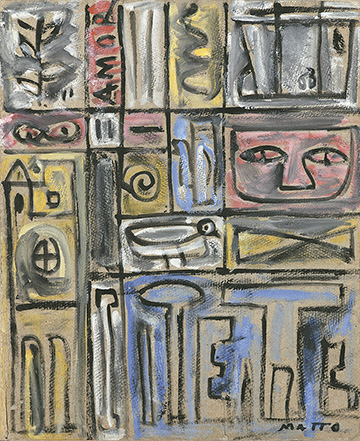

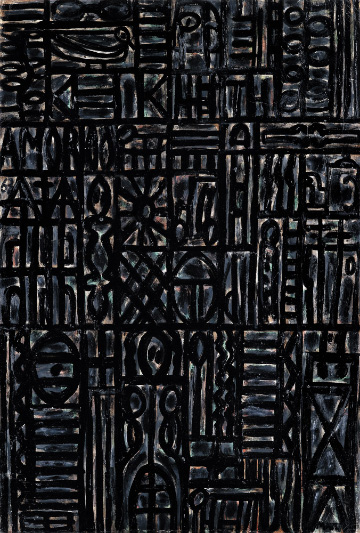

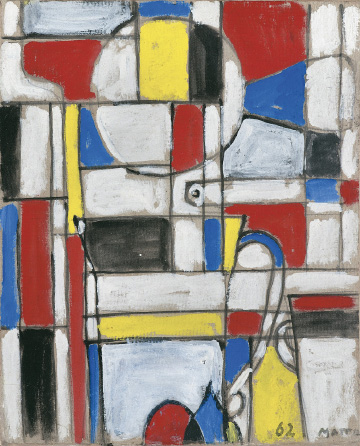

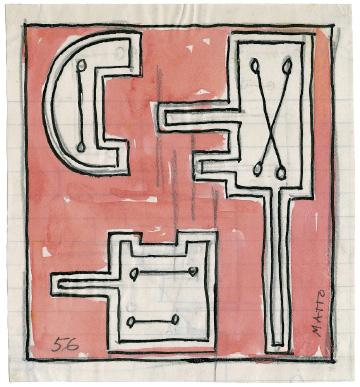

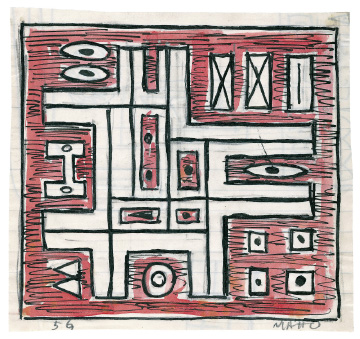

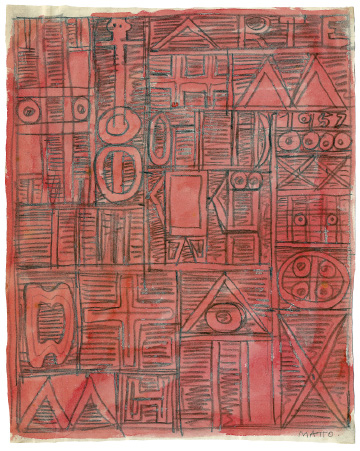

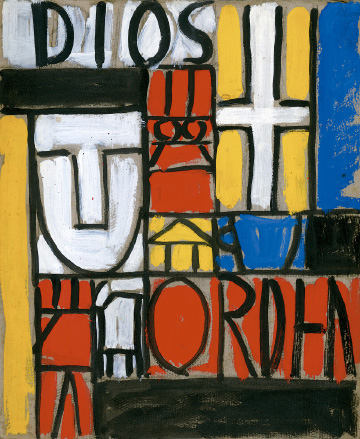

Around 1945 a substantial change took place in his painting and he began a new cycle in his art that would lead him to Constructive Universalism.

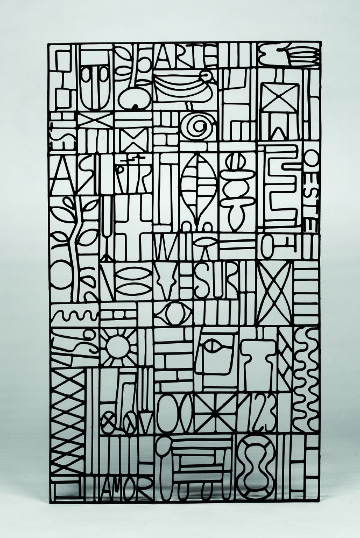

Matto writes in third person: “In the mid-1940s Torres García's influence becomes more evident in his work. The orthogonality of Torres' works and his metaphysical accent would have a big impact on him. Direct study of the art of the Altiplano also influenced his work profoundly. Torres García, on the one hand, and Amerindian art, on the other, would lead him to orthogonality. Going forward, his preference would be for verticals and horizontals in composing structures that would become increasingly frontal, in a very synthetic way."

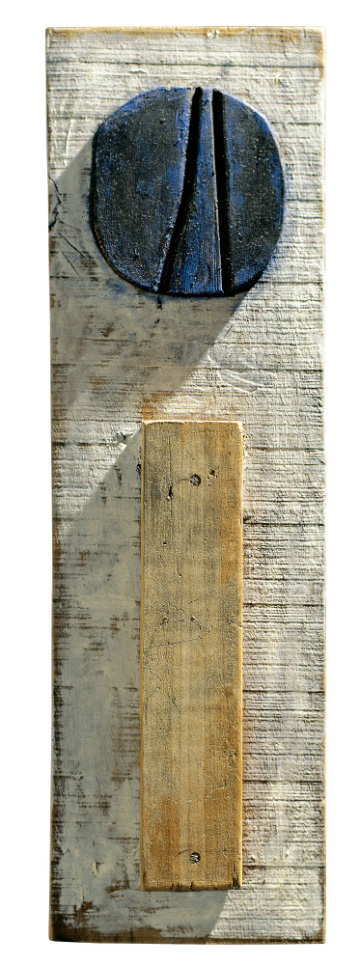

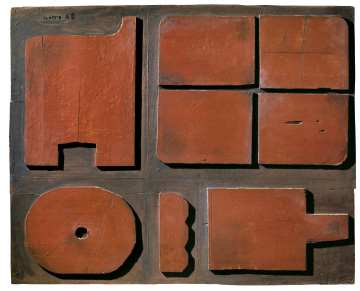

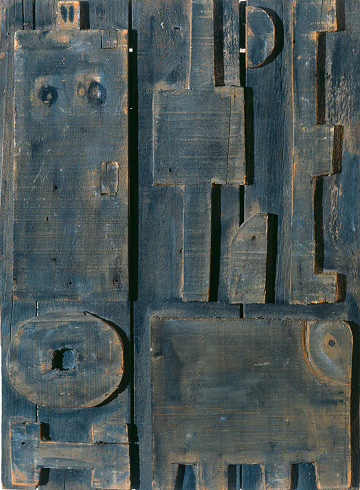

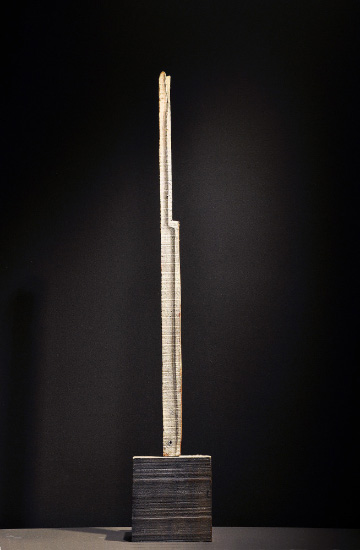

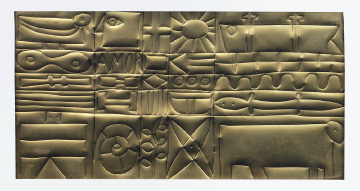

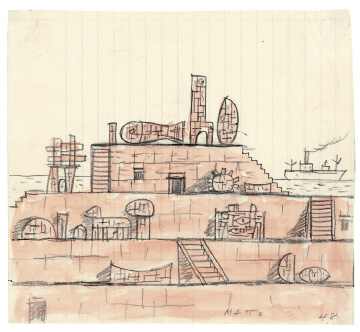

In his mature work he attained unique distinction as a sculptor. He created large-scale sculptural works using wood as his fundamental material.

As noted by Alicia Haber in Matto / El Misterio de la Forma (Matto / The Mystery of Form), 2007): "His monumental facet was a highlight of his creative production; it is what contributed the most elements to the Constructive tradition, what afforded him a prominent place in the history of Uruguayan sculpture, and what evidenced with the greatest conviction his archaic and pre-Columbian ties. The monumental breath of his works denotes his determination to create visual expressions linked to architectural and urban space. Matto saw them as a way to enrich public space, and his concern with formulating an art having very broad projections and capable of enriching everyday life was clear."